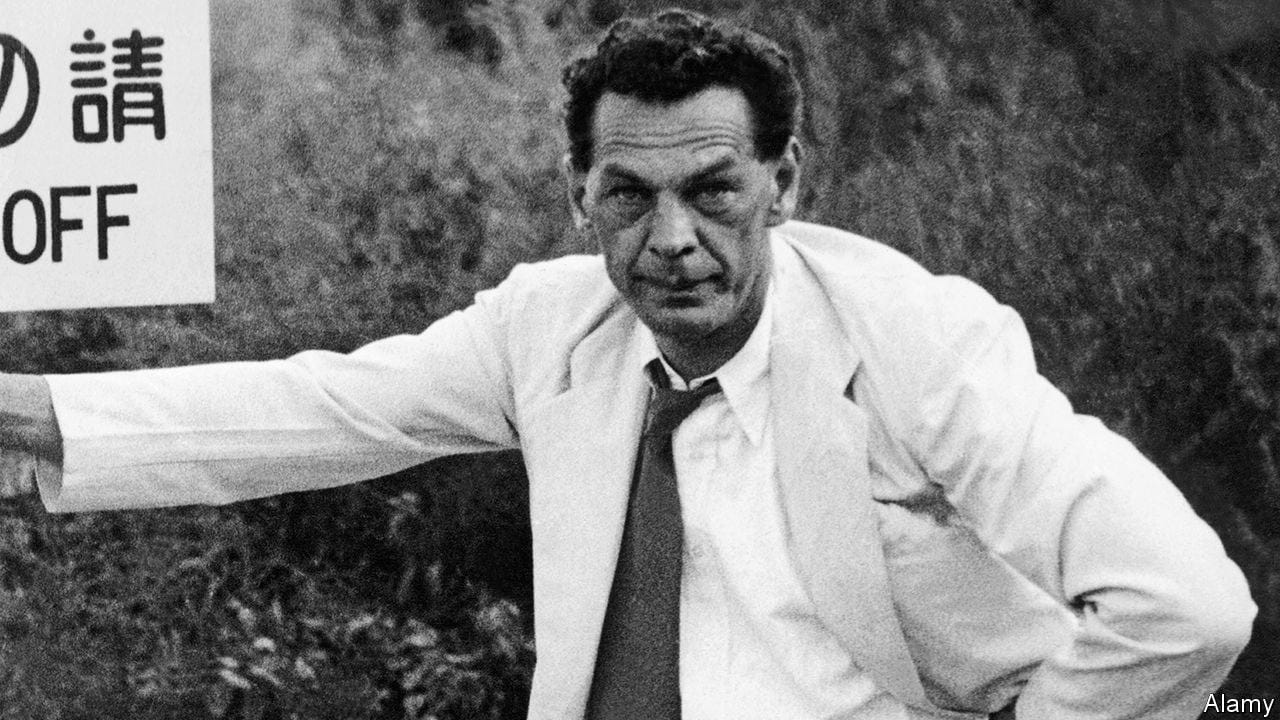

The Silence of Moscow: Richard Sorge, the Spy Who Stayed Behind.

He was recognized for his accomplishments in Russia only 21 years after his execution on the enemies soil.

In 1964, Richard Sorge, the legendary spy who fed crucial intelligence to Soviet military leadership from his base in wartime Tokyo, was posthumously hailed as a Hero of the Soviet Union. It was a hollow recognition—Sorge had been executed by the Japanese in 1943—but it underscored the paradox at the heart of his astonishing, tumultuous career.

Captured by the Japanese, against whom he had spied, Sorge was offered to the Soviet Union in exchange for Japanese prisoners held in Russia. The Soviet response was cold and dismissive: "The man called Richard Sorge is unknown to us." Despite being their most significant intelligence agent in Asia, the Soviets showed no interest. Sorge, it could be said, remained largely unknown to the world for many years, but who was one of the most successful spies in history.

That Sorge received recognition in Russia only 21 years after his execution highlights yet another of the paradoxes that define his story. One of the most striking of these is that, despite being in possession of the most valuable intelligence—advance knowledge of Nazi Germany’s plans to invade the Soviet Union in 1941—Soviet leader Joseph Stalin ignored it, a fatal error in the face of a looming disaster.

Though a staunch pro-Soviet Communist, Sorge’s true driving force was his hatred for Hitler and the Nazi regime. His mission was not just to serve the Soviet Union, but to speed up the defeat of the greatest evil of his time. “Certainly, Sorge's primary duty in Tokyo was to help the Soviet Union ward off a very real threat from Japan. However, he saw Nazi Germany as the most evil and dangerous foe, not only of Russia but of civilization itself.” His warnings about the German invasion fell on deaf ears, prompting him to leak the information to an American journalist, Joseph Newman of The New York Herald Tribune. Sorge also shared crucial intel about Japan’s ambitions in Southeast Asia with Western reporters. Sorge reckoned that it was imperative to alert the Western democracies to Japan's aggressive designs.

Sorge’s life story begins in Baku, Azerbaijan, where his German father worked in the oil fields. Raised in Berlin by his Russian mother, Sorge served as an artillery bombardier during World War I. Wounded and disillusioned, he returned home and quickly became active in the Communist Party.

In the mid-1920s, the Comintern recruited him to become a Soviet agent, and his first assignment took him to Shanghai during the early years of the Chinese Civil War. One of his closest allies there was the pro-Communist American journalist Agnes Smedley, who introduced him to a network of individuals, including a secretive, left-wing Japanese journalist named Ozaki Hotsumi, who would later play a crucial role in Sorge’s espionage operations in Tokyo.

By 1933, Sorge was stationed in Tokyo, tasked with monitoring Japanese intentions toward the Soviet Union. His connections with key figures in the Japanese political and military elite, as well as his ability to infiltrate the German embassy, allowed him to build an extraordinary network of informants. But Sorge’s personal life was recklessly, indulging in alcohol, high-speed motorcycle rides, and affairs with both Japanese and German women, including the anti-Nazi harpsichordist Eta Harich-Schneider. Remarkably, his openly pro-Soviet and anti-Nazi stance was largely overlooked by the German Embassy, who valued his insights into Japan's military strategies.

Key to his success was his deep friendship with Ozaki Hotsumi, who had become a trusted advisor to the Japanese Prime Minister, Prince Konoye. But the most significant intelligence Sorge gathered came from the Germans themselves. Trusted by his German counterparts, Sorge was even sent on a covert mission to Shanghai by his close friend, German military attache Eugen Ott, who would later serve as Hitler’s ambassador to Japan. Sorge’s acquisition of the German cipher tables marked a turning point, and it’s assumed that these keys were passed on to Moscow’s codebreakers.

In 1937, while ignoring an order to return to Moscow for briefing and consultation, sensing that returning to Moscow might lead to his imprisonment or execution, Sorge ignored a direct order to report back. In 1942, after a long period of surveillance, Japan’s counterintelligence finally closed in on him. Despite the imminent danger, Sorge remained defiant, and after months of brutal interrogation, he was executed by hanging. If the Japanese had been able to hand him over to the Soviets, it is likely that Stalin would have ordered his immediate execution in embarrassment for having disregarded Sorge’s intelligence about Hitler’s plans.

Notwithstanding, Sorge’s life becomes a haunting tale of tragic ambiguity. Sorge life was lived on blurred lines between heroism and betrayal, duty and despair. It is a fascinating and thoroughly compelling account of one of history’s most enigmatic spies.

If you’re not already subscribed, kindly subscribe and restack. Thank you!